After recently seeing the documentary ‘Out Of Sight’ originally broadcast in February 1993, I felt compelled to go in search of two featured individuals. Martin Smith, Former Principal of the Deaf Centre, Leeds and Geoffrey Abbot, a profoundly deaf man who had spent over twenty years in Institutional care. Their lives had become inextricably linked, and their stories were remarkable.

Martin Smith, was a champion in his field, dedicating his career to the identification and resettlement of many unfortunate individuals who had unjustly been confined to a life in a secure mental establishment.

Having studied the long term effects of institutional care I found Martin’s work truly inspirational. Through sheer determination he sought out the forgotten in their various hospitals, and brought the light of hope into their hitherto dark acceptance that they would never again experience a normal life in the outside world. He believed that everybody should live in hope and rebuffed the system which had removed the basic right to freedom in many sad cases. Martin tirelessly fought to rescue them and restore them to their rightful place in society. As he recalled……..

….“I would think that you would probably find in most of the major fairly secure hospitals throughout the country there are perhaps one or two examples of profoundly deaf people who had found their way in there with no good reason.”

Martin Smith 1993

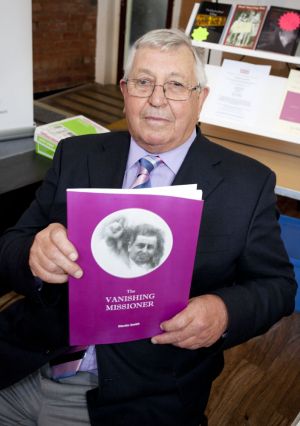

Unfortunately, during my research to follow up on ‘Out Of Sight’, I was to discover that Geoffrey had died some 10 years ago but Martin, a gentleman of seventy years young, did me the honour of granting me an interview at Centurion House. During our 90 minute talk he recalled many poignant stories from his career and memories of people he had met over the years. My sincerest thanks go to him for giving so generously of his time and permitting me to record his incredible journey. His foresight certainly blazed a trail signposting the agenda for change within the mental health system we see today.

You can watch the original documentary ‘Out Of Sight’, by accessing the links on the front page. Parts 1 to 6

you would probably find in most of the major fairly secure there perhaps one or two examples of profoundly deaf people who had found their way in there with no good reason.”

A Brief Overview Of Martin Smith’s Career

Started visiting Menston Psychiatric Hospital September 1957

Visited monthly for 4 years.

Reviewed all cases; Denbigh Psychiatric Hospital, North Wales 1961

Started Deaf club in Hospital.

Visited Deva Countess Of Chester Psychiatric Hospital 1961 – 1964.

Reviewed all cases at Meanwood Park Colony-Started Inmate Deaf Club and began getting people released, including Geoffrey Abbott.

Worked to create service provision in Rampton, High Security Psychiatric Hospital 1980 -1992.

Below is the transcript of Martins recollections, interviewed by Mark Davis, January 2009

“If you think about going into a hospital for the first time, what would that engender? Fear, real apprehension, sense of inadequacy, those things that are very, very powerful were part of the indoctrination into saying that this is a very difficult job you’ve come to, and you’ve got to respect me because I can do it, but you can’t because you are a new boy. You’re a new boy and these are the things that you’ve got to learn and you’ve got to go through the hoops before you can learn”

“I wasn’t taken seriously because I had no sign language. I got status in society because I came from a middle class background, middle class southern voice, toffee nosed fart, and I ‘d just come out of the navy as an officer, a commissioned officer, public school background, a commissioned officer, all the credentials and what was happening to me? I got there and I’d got no speech, nobody could hear my voice a massive language barrier; into a culture I’d never been into, a working class culture that I’d never been into before.”

“I was sent to High Royds – Menston at the end of my first week. I came to work as a trainee welfare officer, specifically with deaf people and in the first week of joining, I arrived on the Monday and I was given what they call a finger spelling card. So I had to learn the manual alphabet, which has got very little to do with sign language, it’s not how deaf people communicate, although you use finger spelling to help them with their communication, it was my first step and they gave it to me but it was not their language that I was learning. Actually nobody taught me their language; that was a kind of secret weapon, which the children of deaf parents had up their sleeve, because they grew up with the language they were completely within it and they had the proper emotional contacts with deaf people because they could be looked at, oh yes his mum and dad were deaf and dumb, as they used to be called and those people could actually get inside the language and they could create the emotional strength of a relationship, they could feel their emotions and they could produce them. I couldn’t. All I Had was a kind of straight face and still had a naval officers voice going on in my head, I wasn’t a tactile human being like deaf people are who produce the language.”

“When you saw me talking earlier you saw a huge amount of body language and attitudes, nobody taught me that, it was just something that was part of my being. I was just a straight Englishman with a straight Englishman’s voice and I could talk like this, like a missionary, like a vicar and my book is called “The Vanishing Missionary”. I went in to this work and then actually discovered, accepted everything I was taught, bit by bit I became passionate about it, particularly the mental hospital bit, once you get in side there and you see what’s going on, so many games just so many clues, the ultimate in repression, it’s total power of one group over another, leaving them with no hope whatsoever, with nowhere to go and nothing to do.”

“And people, just completely institutionalised; you only get little glimmers of people resisting that like you did from the epileptics, little glimpses coming out, most of the time, you went in there and for a lot of folks it took all of the pressures away, that’s the balance of the thing, it took all the pressures away; if you were ill and you had a clinical mental illness and it came and it went, you swung, you changed, you weren’t always mentally ill, you had better periods and you were depressed or not depressed.”

“To go into a hospital and be brought back in and everybody would say “Oo hello” and you’re phew- back down to your fags and you’re back down to your cups of tea and you’re back down to not having to communicate unless you want to, sitting in the same chair that you were and you’ve gone right back to that kind of un-pressurised situation”.

“And when they got rid of places like High Royds, they got rid of a lot of the power that got to be exerted and got exercised, but their value was considerable but not recognised.”

“From my experience at Denbigh Psychiatric Hospital and Deva The Countess Of Chester Psychiatric Hospital and some of the things I did at Oldham, I decided when I came back as the Principal of the Centre for Deaf people in Leeds which was part of the Leeds Incorporated Institution for Blind and Deaf people, it’s origins went back to 1854, so well established; it became local authority supported after the war 1948, the local authority then had responsibility to create facilities for deaf people, that was the point the centre started to get money from the local authority and that changed the way it operated.

Well it didn’t actually change the way it operated, it changed the way that they were funded, because they didn’t ask and they didn’t know how to ask any questions about how a service should be administered and as usual because of the communication barriers which were actually made stronger by the bosses of the organisation because they didn’t want their clients telling the local authority what was going on, and there were no deaf people on the committees, management committees, that was because they couldn’t manage and they weren’t responsible enough so you kept them there and so the local authority gave money to the voluntary organisations and they didn’t ask any questions about it. “Just do the right things by us”

“So you had a lot of freedoms and I just decided that I would go to Meanwood Park Colony. I went to see the superintendent, Douglas Spencer, got on very well with him, deep down he was a very nice human being and he just said carry on so we circulated all the wards and said that if you got any deaf people or you think that people have a history having been in a school for the deaf or deaf people, wearing hearing aids, bring them in. So I had two or three days, just sitting at a desk with different wards or villas bringing in their folks and that’s when I found Geoffrey Abbot.”

“Because Geoffrey came in and I signed to him. My signing was getting better. Geoffrey could sign language he had been to a school for the deaf and he’d got sign language and I signed to him and he responded and we started to joke together and there was Geoffrey, he was in lots of ways quite happy and it took in fact, 7 years to get him out of hospital, because nobody wanted him to go, he was too useful to people and by that time I’d moved on, I’d created this club and ran it met the deaf people there and got to know them and tried to put the word around the hospital who these folks were.”

“Eventually we got Geoffrey out and into a hostel with other deaf people and got him coming to the Deaf Club and he began to build a life with other deaf people.”

“There was resistance to him leaving because he was too useful, he’d got a lot of friends in there, he’d got friends who just visited the hospital, who he knew, he was very observant, I know people now who used to go there voluntarily years ago, who saw Geoffrey and got to know him there, he was a definite personality, got a lot about him and that of course was the reason he went in, ‘cos he was a sparky guy and he used to fight like hell, he was a difficult guy with this big personality, he used to react to you in a marvellous way and people just loved him, so getting him out was a kind of mission and it needed to be done and you had to nudge away and nudge away, but eventually he broke down and came out, we got him into a hostel.”

“I think people within institutions like that have this power to control events and it takes an awful lot of time, for them to feel that you are a recognisable human being somebody who can be trusted and valued enough to look after Geoffrey, and that was probably a lot of it and when he came out he obviously had to go through a great deal of difficulties in order to adjust, he always had this place and he had to go through all the experiments about himself, generally he had to go through a range of different experiences. Like in the hospitals, you got the corridor livers, they lived there and they stay there, they operate in the corridors, you can walk over them, they’ll look at you, they’ll look at each other, they will know what the routines are and they will feel comfortable in the corridor, they’ve got a certain degree of freedom, and that’s all that there is for them and they’ve come to be institutionalised into feeling that freedom and not going any further.

Coming out of hospital is like ricocheting down a corridor and at the other end there is a light, which is kind of like an unknown light and a frightening light and in order to get out into that light you’ve got to ricochet down that corridor in order to get there, so you bounce against society on either side, you meet prejudices, you meet attitudes which you don’t know, you meet the rules and regulations which society lays down, you don’t know those so you have to experience them and react against them and to learn how to cope with them and reinforce them so that they become part of your survival technique. So you’ve got the survival techniques that have got to be learnt when you come out of hospital, it’s not a matter of everybody saying “Whey -hey” We’ve done it.”

“The kind of people I got out of High Royds, the chap who came to work as the caretaker, I think he’d had 14 years in there, I got him out in 1966/67 because I started visiting him in 1957 and I visited him for four years. I came back from when I was away in North Wales 5 years later and he was still in High Royds and I was trying to get him out and the caretaker’s job arose at the Deaf centre. I said come on work here and what he had was ready access to what we had here; other deaf people and he had a safety net and he kept going with that safety net and he had quite loving caring parents. He came out and he worked perfectly well as a caretaker. He cleaned and got the boiler going and all of those kind of things and eventually packed it in and got married and went to live in Wakefield, a real success story.”

“I remember when I used to meet the caretaker out in the gardens at High Royds quite close to the white former Superintendents house to the front. There was nothing the matter with him, he wasn’t in a locked ward or anything. Ward 14 was the secure unit, on one occasion in my early days at High Royds I was attempting to get to Ward 14, at the time money was short so I would often buy clothes from the second hand shops, that particular day I was wearing a black mac similar to the type worn in the hospital. A rather large male attendant approached asked me where I was going, as I explained I was heading to Ward 24, he presumed me to be a patient and promptly frog marched me to my destination.”

“Eventually there were other people who came and worked with me who got other people out who used to come to that club, in particular someone who had got sight loss as well, I didn’t get them out but that was the kind of exit basis, their sensory condition had been important in the reason why they had been put away in the first place, they couldn’t have a response to what people were doing.”

“The 1959 act had no impact on me whatsoever.”

“Nobody representing Geoffrey and the conditions at home meant that there wouldn’t be any enthusiasm from his parents to get him out, they’d got a settled home life and Geoffrey had always been a difficult person.”

“Life for deaf patients in the institutions had been pretty grim. They were moved from one ward to another, except for people like Geoffrey who had got jobs, they worked in people’s homes. At the entrance to Meanwood Park there was a lodge, he worked in there. There was quite a big social life in Meanwood Park the cricket teams, a lot of Downs Syndrome people that could take part in games.”

“All the deaf people were in different wards, but they weren’t brought together, when you think conditions of the villas, there were little outbreaks and you could always tell if someone was going to have one and everyone knew what to do, and there were little rooms, little secured rooms, they were lock up places just as there were in High Royds and also in Armley prison. In High Royds there was one occasion when one person was stripped and put in a cell and I’m sure that kind of thing went on in Meanwood, the possibilities of abuse and cruelty were enormous, I’m not saying that I have seen instances, but the possibilities were enormous.”

“There were 20 Epileptic Patients in the cage that I saw at High Royds, you went in and it was on the way through, it wasn’t a closed ward , it was a pen, on the right hand side as you walked through into another area as you were going through down the long corridor, going towards the annex and they were literally in this cage and I said who are these people and they said these are the epileptics. As I walked past them they were singing a song about being in Menston:-

THE EPILEPTIC SONG

Buggered in the morning

Buggered in the evening

Buggered at supper time

If you get stuck in Menston

You get Buggered all the time.

This was sung to the tune of a popular song of the time “Sugar in the morning.” Roy Orbison

“What I did learn are that those places are very sensitive and you’ve got to work your passage.”

“There is a kind of philosophy, about the situations, and those people that lived on corridors and their way out, kind of trying to get descriptions of what was going on and trying to get your mind around what was happening to people, rather than they’re in there and they’re coming out, what’s the processes for coming out, what are the human interaction going on around it, what are the non verbal insights into what’s happening. There was one very important occasion that I recall regarding somebody that had been in a mental institution since he was six and the local authority whose responsibility he was said will you go an look at him because we’ve been paying a lot of money to the organisation that is looking after him, he’s now about 22 he’d been in since he was six.”

“So I went to see this guy down in St.Lawrence’s hospital in Carsholton in Surrey and I found this guy and they took me to the ward, here he is, I signed to him and there wasn’t anything, no sign language there at all, he’d never been with other deaf people and he grabbed my face and twisted it and looked at me and I thought what do I do about this and I put my hand up and I stroked him and just try and show some kind of feeling. Some kind of affection and he thought this was alright, this was in the purest sense that one could get and he then grabbed me by the hand and he took me on a walk around the hospital, profoundly deaf, he’d got, he’d obviously got myopic vision, he’d got real tunnel vision and he then took me for a walk which was utterly sensorial, in so much as that he took me down a corridor and when we got to a radiator he stopped and warmed himself, when we got to a window, he got the air going in and blowing on him and everything he did was sensorial, it wasn’t anything to do with anyone’s speech or words or anything, he was a complete sensorial animal and he was also quite amazing, he wasn’t violent, he was autistic in the extreme but like many autistic people he had got one area where he was brilliant, half of the professors in this country are autistic, and his one area was playing music, he could actually pick out tunes on the piano and he could hear them and he could manage that, he got no speech, very little sight but he could just pick up a piano. I wrote the report about him in these terms, that he was a sensorial animal and they seemed to understand and said can you get him out. So they gave me carte blanche, as did the hospital because they knew him and they knew he shouldn’t be there,”

“So I got him out of the hospital and into a specialist rehabilitation place and the only possession that he had got was a tie that his mother had given him and eventually he was making quite a lot of progress, he seemed to be happier and had much more freedoms, in the end tragically they took him to Majorca and crossing the road, he didn’t know how to cross roads and the bloke that was crossing the road and holding his hand, he stopped and went back and the other bloke came and a car came along.”

“It was quite a remarkable experience to come across someone like that. So far away from everyone else, with no words, no other descriptions apart from cold, food, touch, smooth rough all those things and he just wanted to take you around his sensorial journey, if you shared it with him you were sharing his life and he liked that. Something there that had just trickled through.”

“I keep it in these terms, what the hell have I learned doing this job and what would I have learned if I had stayed in the navy, I’d have learned nothing about communication, working class life, all the joy I’ve had communicating with people, I’ve had a fantastic time that I wouldn’t have got if I hadn’t have done this job. I’ve gone into every sector of society and gleaned so much from it.”

Interview with Martin Smith, January 2009.

About The Deaf And Blind Society Leeds.

Leeds Society for Deaf and Blind People has existed since 1866. Throughout its long history, the single objective has been to respond to the expressed needs and aspirations of deaf, hard of hearing, deafblind, blind and partially sighted people. This has been achieved by the active participation of sensory-impaired people, both as members of committees at every level and as members of staff.

The success of the Society is without doubt due to the active pursuit of this policy. However, sensory-impaired people recognise the value of the large number of people who have given and continue to give their time and talents in a voluntary capacity, and this valuable input has been a significant factor in the progress of the Society.

There are few, if any, other voluntary societies which provide services for both sensory impairments. The reputation of Leeds Society for Deaf and Blind People is virtually without equal in this regard, and the benefit of our advice, opinion and experience is sought by people throughout the UK. The Society recognises that its long partnership since the 1950s with Leeds City Council Social Services has also been a significant factor in this success.

The Society is neither complacent nor static. We may never achieve perfection, but we can continually strive to improve, and this will be achieved by listening to our members and service users. By consultation and cooperation, we shall ensure that we enable each person to have the opportunity of choice, leading to achieving their personal potential and independent living.