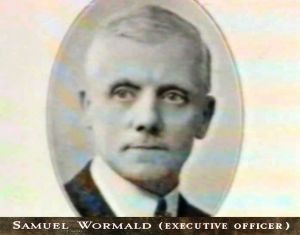

Wormald, Mr. Samuel

Leeds 1937

Eugenics Society Member 1937

Personal: Executive Office, Mental Deficiency

Act Comm., 38 Park Square, Leeds 1938

Source: ESAR 1937

http://www.eugenics-watch.com/briteugen/eug_uz.html

Samuel Wormald rounded up more than 2,000 people in the Leeds area

…………………………………………………………………………………….

Stolen Lives: Featured on channel 4

Ida Norman (IN)

Geoffrey Kaye (GK)

Ivy Kennedy (IK)

Mary Clarkson (MC)

Maggie Potts (MP)

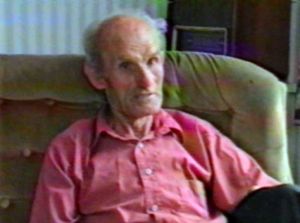

Ida Norman (IN) -I was coming out of mill, Friday night, five o clock we left, now I were excited cos I’d got my first wage you see. Then I was going down the hill through the tunnel and this man at the bottom, they called him Wormald…a lot of people…. He’s dead now. He said come on you’re going in my…. I said look I’m not going in your car. I said you’ve been after me too much. He had a job to get me, but there was nobody you see.

Geoffrey Kaye (GK) – Going back home from school that’s how he got me. He had a car, oh he said we’re going for a ride. I said I know what ride is, where you’re taking me, you’re not going to take me. He didn’t say anything, he just took me, to that place.

The place Ida Norman and Geoffrey Kay were taken to was Meanwood Park Colony for Mental Defectives which had opened on the outskirts of Leeds in 1920. The man who took them there was Samuel Wormald, who saw himself at the vanguard of a movement to remove anyone with a disability from society and wrote at the time: “ By being allowed to repeat their type, the feebleminded are increasing the ranks of the degenerate and wastral classes with disastrous consequences to the entire community. In the 1920s and 30s Samuel Wormald rounded up more than 2,000 people in the Leeds area, school children, factory workers and mill girls found themselves being taken to Meanwood.

Seventy years later, Meanwood is closing as part of the national plan to move everyone back into society. There are still 200 people living here waiting to return but now their rights as individuals to live in homes of their own rather than institutions are being threatened. More and more voluntary and private organisations are entering the community care field looking for economies and profitability and there’s a disturbing trend towards setting up large village type communities. There is even a campaign to keep Meanwood open as such a village community.

Maggie Potts is a Clinical Psychologist involved in helping people to move out of Meanwood.

Maggie Potts (MP) – The plan to close Meanwood, the first one was put forward in 1984 and there was a counter proposal that the site should become a village community and there are a number of such communities throughout the country. The irony of that is that Meanwood Park was originally set up as the Ideal System , that this form of care was a real advance on the old fashioned institutions, that here you had separate villas, in beautiful grounds which they are, with beautiful trees. It was very self sufficient, it had it’s own farm, people worked, but people were not there of their own free will and the same thing applies to village communities today, people are not there because they want to be there. And if we start saying that these people are very handicapped, they need to be together and they need to be separated and cared for specially, then what we’re saying really is that they’re not people like us. They don’t have the same needs as us and that was were we started. That this was a humane way of caring for people who really shouldn’t be out in the community.

In the early part of the century it was believed that a vast range of people should be put into institutions for life. The Mental Deficiency Act of 1913 had established four categories of people to be institutionalised: moral defectives, idiots, imbeciles and feebleminded. Under the catch all phrases of “Mental Defective”, anyone who was poor, disabled or had a learning difficulty became a potential candidate for removal to an institution. In Leeds Samuel Wormald was in charge of enforcing the act. He made the mills one of his stalking grounds. Ida Norman had attended a special school as a child but was enjoying her job at the mill.

IN – Oh they were lovely girls, lovely and they didn’t call you, they were lovely. They were nice wi’ me. I used to go out with them, used to go all over with ‘em. Mind you they liked you to swear in them mills, cos you couldn’t do nowt else, you couldn’t hear yourself speak. Oh no, I liked mill, it were very noisy, but I liked it. I liked every moment of it.

Wormald tried to catch people when there was least chance of resistance from family and friends. In 1932, he got Ida on her way home from the mill and took her straight to Meanwood.

IN – Oh and I cried my eyes out. I couldn’t see anybody for crying and when I got in Meanwood, I felt awful and it got worse still, they said “Come on, you’ll be alright”, I said “ I’m not stopping here, I tried to get out but I couldn’t cos they locked the door you see.

Under the act, children were just as likely to be put away. Geoffrey Kay was picked up off the street by Wormald when he was on his way home from special school, he was just 7 years old when he was taken to Meanwood.

GK – I was crying, I didn’t know anybody. I were right nervous and shivering. I were that cold I didn’t know what to say to myself. Cos I didn’t know the place and what it were like.

Unmarried women who had babies were also targeted. When Mary Clarkson gave birth to her daughter she was sent straight to Meanwood and never saw the baby again.

Mary Clarkson (MC) – I couldn’t say nothing, I were full up – I could hardly talk, cos I were nearly starting crying because they would have been wondering where I were. I couldn’t even go home to pack up, to pack me other clothes up.

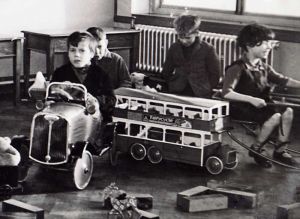

Once at Meanwood, everyone was put into a colony uniform, assessed and then classified. Assessments were a mixture of IQ tests and general knowledge questions.

MP – The criteria used for assessment seemed to be extremely arbitrary with questions being selected to demonstrate the limit of people’s ability and they would be used to shown that people couldn’t do various things and therefore was feebleminded and therefore had to be in an institution.

IN – They used to ask you different questions, what we remember, you know and money, they used to put money on the table and do it and read. I were a bit backward that’s why, that’s all I was. That’s why they put you in there cos you were a bit backward and there’s plenty more outside like it.

MC – They gave me some beads or summat, baby beads or summat, they were only tiny ones. How do you expect me to do all these, I said, I can’t get a needle through all these so I told ‘em to do ‘em themselves. I put ‘em down and left ‘em.

Mary, Ida and Geoffrey were all certified as feebleminded. Every five years, inmates had the right to have their classification reviewed and to be considered for release but even those who had the support of their families found themselves trapped.

IN – We couldn’t get out love. They had us committed. They had court to us but they couldn’t get us out. I went to town hall and me mother went to town hall over me but they couldn’t get me, wouldn’t let me go.

Once classified the inmates were assigned to live in numbered villas. Up to 80 people, ate, slept and lived in each unit. With more than 600 inmates and little money for their upkeep, places the size of Meanwood, relied upon the labour of all able bodied inmates regardless of their classification.

MP – The ethos came down to economics, care and control at minimal cost, so you had a minimal staffing level, supported by a number of residents who made the beds, looked after the least able, who served the meals, who worked in the laundry, who worked the market garden, who worked in the kitchens, who were porters and cleaners and cooks and they actually kept the institution going.

After being sacked at her job in the mill, Ivy Kennedy was classified in Meanwood as feebleminded.

Ivy Kennedy (IK) – I used to get up at half past six and then after us breakfast we went upstairs and made all the beds for them that couldn’t do it for themselves and if they were short of domestics we used to do cleaning. I was made to scrub the floors and if you didn’t do it you didn’t get nothing to eat. They took your meals away, nothing.

IN – They said come on you’ve got to get all this coke in. I said, I can’t, I’m not putting coke in. I’ve never been used to putting coke in. Well if you don’t, you don’t get no dinner, no tea, if you don’t out that coke in. They were nearly like a prison, cos you’d no freedom at all.

MC – When we went up for a bath, there were nurses who drew the water for you, you used to line up in a line outside till you got your name called out. They were with you all the time in the bathroom, sat there watching you, getting a bath. I said to one of them “Can’t you trust us?

MP – The aim when people came was to destroy their individuality, everything was recorded so there was a bowel book and a menstruation book and a fit book and a bathing book. The whole system was geared to people being controlled and the only way in which those controls could operate was by a system of punishments and that system seemed to have operated quite arbitrarily when you look at the records:

“Very insolent and rude and refused to do her work”

“Kept in bed for two days and conduct awards reduced”

“Very insolent and refused to work properly in the laundry – conduct awards stopped for a week”

“Refused to work in the laundry, put to bed for two days, still very obstinate”

There were other forms of punishment that went unrecorded. When Geoffrey was still a boy he was made to work on the building of the perimeter wall which divided Meanwood from the outside world. The stone was dug from within the grounds and the entire wall, 3 miles long was built by hand.

GK – You had to carry wet sand bags on your bare back. Heavy ones n’ all. I had one of them big ones, you know, I didn’t carry two. I carried one. It was all wet and slippy. If you stopped, bang with the cane or a whip across your back. We were getting punished, that’s what they were doing, they were punishing. I didn’t like it at all.

When Meanwood Park Colony was built, every villa was designed to have a number of what were known as side rooms, in which inmates who rebelled were punished with periods in solitary confinement.

IN – I used to take their plates up with bread on, underneath the side rooms, the padded rooms with a little window in. I used to feel sorry for them. They used to scream and scream, shocking.

IK – They left me in there for a month, no pleasure, no nothing. They had the shutter locked, door were locked, you couldn’t get no air, you were suffocating and I was on the floor, you see, I couldn’t move because they gave me injection to calm me down, I was going that mad and this thing were cutting all me neck. I couldn’t get away and I, then I stopped there and I said when they gonna let me out, I says there’s no need for it but one of nurses came up and she said “ You’re not coming out of there, you’re not fit to come out.” I says “What?, I says I am fit to come out.

IN – Oo Ivy, she were never out of the side rooms Ivy, mind you it were the staff that set her on though, it wasn’t her. She was alright, she used to sit with me but they set her on. Oh yes, she used to be a nice girl and then she went right low, she went ever so low love, well I would have thought I would but I didn’t. I said Ivy you must buck yourself up love. She said they won’t let you love, look at my hands again, all bandaged up she said.

IK – Oo I felt terrible, awful, I were upset all the time, crying. I says oo, it’s disgusting this, disgusting, what they’ve done. I were partly always in that room, never out,

In spite of the constant guard under which the inmates lived out their lives there were daily attempts to escape. Very few actually managed to get away for good but those who did were always remembered.

GK – Jim Barker, Tom Boller, Maurice Coin and Fred Avyard. They were getting accused in the villas of what they hadn’t done. That’s how they took a walk and they never came back. They didn’t tell ‘em where they were going. They got a job and look where they are now. Free man.

For hundreds of inmates, Meanwood Park Colony remained their home. The injustice of the whole system wasn’t recognised until 1959 when the Mental Health Act stated that only those who were a danger to themselves or to society could be detained any longer. Overnight the vast majority of the inmates at Meanwood became technically free to leave but it wasn’t until a real effort was made in the 1970s and 80s to resettle people under community care that they were finally given back their freedom.

IN – Couldn’t believe it love. When they told me I were going to a flat of my own I couldn’t believe it. I did it. I didn’t bother about the neighbours or anybody else I just washed and put me washing out and they would have said “She’s not mental, look at her washing she does.”

IK – Oh I was right chuffed. I was glad to get out. Yeah. I said I’m free.

GK – Oh I was right happy. I were glad to get away. I were right cheerful. Oh Thank You I’m going now. Got all my things packed up what I had and that’s it.

MC – I were glad to get out of it. It wasn’t the place. I didn’t not like the place but it were some of the staff and villa I were in that I didn’t like really.

At one time nearly 1,000 people were housed in the 17 villas at Meanwood. Under Community Care many of those who were classified as feebleminded more than 60 years ago have been released to resume their lives in society. There are 200 people still left here, the last waiting to return. While much has changed in the way that care is now offered, aspects of the old institutional system remain.

MP – Inside the institutions and we’re seeing it with some community care settings as well, is again the system of control so if people behave “badly” in inverted commas, they’re likely to have privileges stopped. In these days it may be that they lose their television for a week or they lose their radio or a treat is stopped rather than they’re put in a side room or kept in bed, so the punishment is lesser in that extent, but it’s still devastating in it’s effects and it’s still the idea that the staff are in control of a person.

Some of the people still here were originally put in and classified under the Mental Deficiency Act of 1913 and now as they prepare to leave they are once again being assessed but the assessment for their return to society is still not based on their rights as individuals.

MP – When people first came here they had to fit in to whichever villa was decided for them. There was no choice. We’re now at a situation with resettlement into the community and with voluntary and private agencies springing up everywhere that people are assessed and then they have to fit into whatever is deemed to meet their needs. Now a vacant bed costs money and a void has to be filled and moreover it has to be filled with someone who needs that level of care. So if there’s a vacancy in a place the first consideration is who is the person economically who can fill that place rather than the wishes of the individuals. It is a mark of a civilised society that people are recognised as having a right to be individuals, as having a right to a home and a right to possessions and that should be the basic rights in a civilised society. And we’re a very long way from people taking control and taking charge with help and with support in those very basic and fundamental aspects of life.

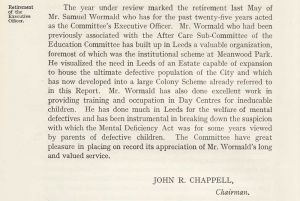

Ida Norman lived for six years in her flat before moving to an old people’s home. She spent 39 years in Meanwood.

IN – We beared it something terrible we did. Just tried to be cheerful. My life was wasted. Anybody would say so when they know how long I’ve been. A life sentence I did at Meanwood. More than ever.

Ivy Kennedy lives alone in a flat. She spent 38 years in Meanwood.

IK – My life was wasted. Stopping in there all that time. I was 19 when I went in. I didn’t think I’d be there long but all my life’s gone. I could have been happy.

Geoffrey Kaye now shares a flat with two friends who also lived most of their lives at Meanwood. Geoffrey spent 48 years in there.

GK – I’m not going to do another sentence. I’ve done enough – 48 years – I’ve had my service. I shouldn’t have gone in first place. I should have been doing something else.

Mary Clarkson is now 86 and lives in old people’s home. She spent 61 years of her life in Meanwood.

MC – I thought I’d get out earlier than this. I do what I like on my own and go shopping and bring things in. When I’m sat thinking about it and I’ve nothing to do, I sit and weep you know, tears are coming down and I’m thinking about allsorts. I’ve cried myself to sleep some nights.

When Meanwood Park Colony was set up over 70 years ago it was thought to be the ideal system of care for anyone with a disability but the thousands of people who were detained there were denied the right to chose how they live their lives. When Ida & Ivy were released in the early days of community care, they were given back that fundamental human right.

MP – There was a period of great optimism in the 80s where individual rights and needs were the governing principles. I feel there is a danger that we’re going to lose that because of economy and what the taxpayer will pay is again becoming the predominant theme in community care and what I hope is that the stories of Ivy & Ida will help us not to repeat the mistakes of the past, that history won’t repeat itself and we won’t set up nice village communities which rely on able bodied inmates to do the care and which deny people freedom and basic rights whatever their level of handicap.